Georgia

EV Charging in Georgia -

Georgia’s official stance on electric vehicle (EV) charging station deployment in 2026 reflects a strategic, data‑backed commitment to expanding infrastructure while leveraging federal funds and private partnerships. Through the federally funded National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program, Georgia has been allocated about $135 million to develop a reliable network of public EV chargers, particularly fast‑charging (DCFC) stations along major alternative fuel corridors. In late 2025, the Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT) awarded $24.4 million in NEVI grants to support 26 new DC fast‑charging sites statewide, each with multiple high‑speed chargers to serve drivers 24/7, demonstrating progress toward a continuous, dependable charging network.

These awards represent the second deployment round after an initial 2024 investment and aim especially at closing coverage gaps in rural and underserved regions.

Beyond infrastructure deployment, Georgia has also adopted state tax incentives aimed at encouraging private investment in charging station installation. Eligible businesses can claim a state income tax credit of up to 10% of the cost (maximum $2,500) for purchasing and installing qualified EV charging equipment, which may be carried forward if unused. This credit is intended to stimulate broader participation from local enterprises in expanding public access to charging. Additionally, the Electric Mobility Innovation Alliance (EMIA) under the Georgia Department of Economic Development actively studies charging infrastructure needs and policy recommendations to guide future deployment strategies, including suggestions for urban, highway, and destination charging solutions.

At the regulatory level, Georgia has passed laws shaping the competitive landscape for charging infrastructure, such as limiting utility use of ratepayer funds to subsidize EV charging to avoid customer cost burdens and promote private sector participation, while allowing Georgia Power to serve select rural areas. These regulatory frameworks aim to balance infrastructure growth with market fairness, even as broader federal EV policy experienced ups and downs (including pauses in NEVI guidance in early 2025 before resuming). Overall, Georgia’s approach in 2026 combines federal funding utilization, state incentives, targeted regulatory adjustments, and collaborative planning to expand EV charging access, support EV adoption, and enhance transportation electrification across the state.

Solar Power in Georgia -

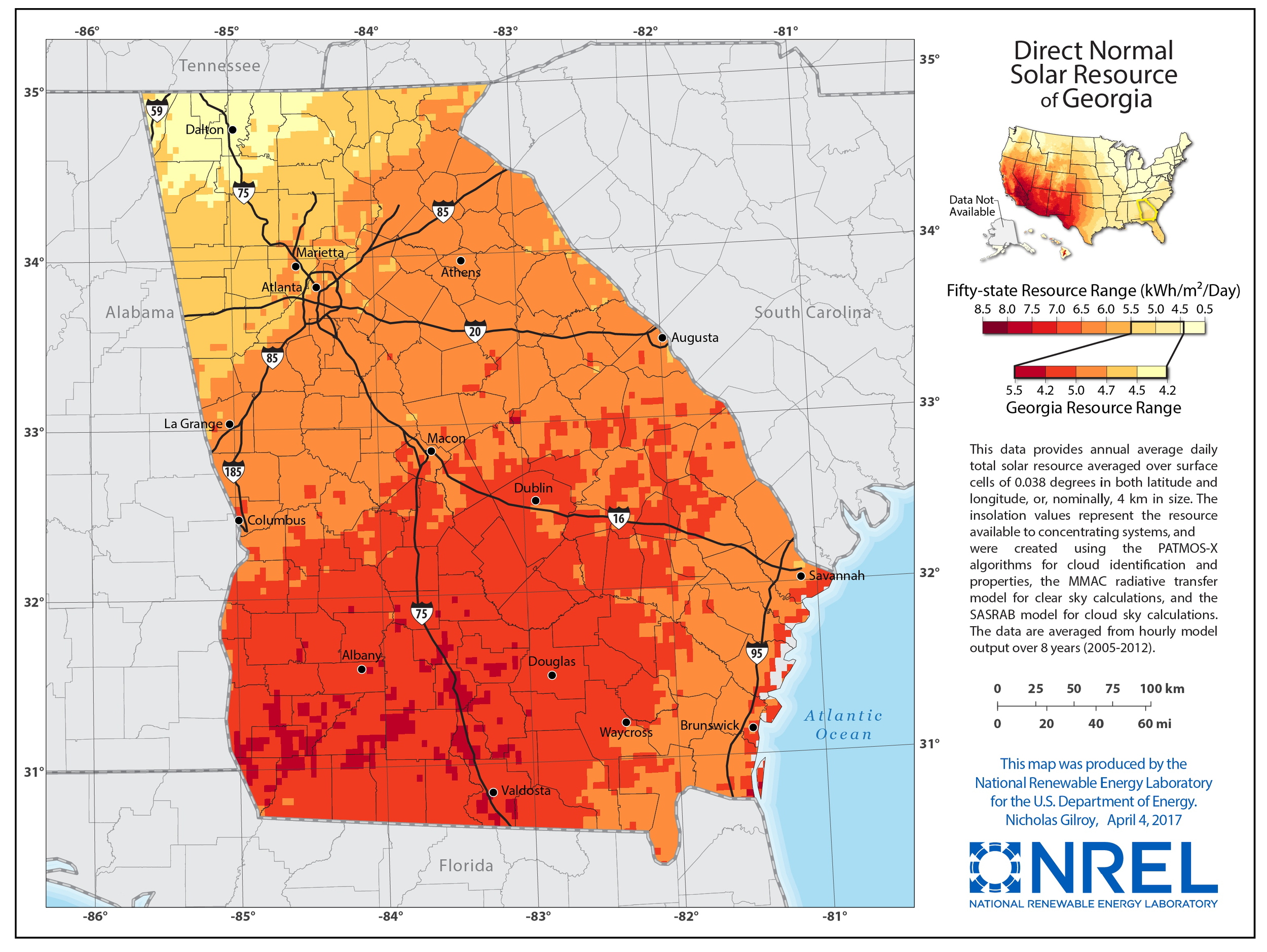

Georgia’s policy environment in 2026 reflects a cautiously expanding but politically mixed stance toward commercial solar power projects. At the heart of state-level support is the regulatory pathway established through Georgia Power’s Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) and related initiatives like the Clean and Renewable Energy Subscription (CARES) program. In 2025, the Georgia Public Service Commission (PSC) approved five new utility‑scale solar power purchase agreements totaling 1,068 megawatts (MW), selected via competitive bids to serve commercial and industrial customers looking to procure renewable energy shares. These projects are part of ongoing procurements under the 2022 and 2023 IRP directives, and Georgia Power has issued further requests for proposals targeting up to 2,000 MW of additional utility‑scale solar, including solar‑plus‑storage options, with commercial operation dates anticipated as early as 2028.

Despite these forward moves, Georgia’s broader policy framework and utility incentives lag behind many other states. The state as of early 2026 offers limited direct tax incentives or rebates at the state level for commercial solar developers, relying instead on federal investment tax credits (30 % ITC) for businesses that own systems, while net‑billing rather than full net‑metering can limit the economics for larger commercial rooftop installations beyond 250 kW under Georgia Power’s tariffs. Additionally, legislative activity has focused on structuring solar power facility agreements and land‑use protections—such as decommissioning requirements under the amended Solar Power Free‑Market Financing Act—rather than aggressive statewide solar incentives.

The stance toward commercial solar is also shaped by regulatory politics and competing energy priorities. While utilities and the PSC officially support incremental solar additions, critics—including clean‑energy advocates and some nonprofit groups—argue that Georgia’s trajectory still underutilizes solar relative to projected capacity needs and the rapid growth of electricity demand (notably from data centers), and that the state remains low in per‑capita solar deployment. There has been pushback on community solar markets historically, though recent utility‑negotiated pathways suggest possible future expansions in customer‑sited commercial and community solar participation. Overall, Georgia’s stance in 2026 is one of pragmatic inclusion of commercial solar in utility planning frameworks—backed by measurable capacity targets—but with relatively modest incentives and ongoing debate about the balance between traditional utility expansion and renewable dominance.