West Virginia

EV Charging in West Virginia -

West Virginia’s overall 2026 stance on commercial electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure remains largely grounded in participating in federal programs rather than creating extensive state‑level incentives. The state is fully engaged with the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) Formula Program, which provides dedicated federal dollars to help deploy a network of EV chargers, especially along key travel routes. Under this plan, the West Virginia Department of Transportation (WVDOT) is focusing initial funding on building out stations every 50 miles along designated Alternative Fuel Corridors on interstates such as I‑64, I‑77, I‑79, I‑70 and I‑81, with each site targeting a minimum of four 150 kW fast‑charging ports. This first phase is intended to help long‑distance travelers and meets federal NEVI spacing and capacity requirements, while a second phase plans to extend charging into more community‑based locations like parks, colleges and rural areas once corridor coverage is complete. Projections from the state’s NEVI deployment plan estimate that current construction will create hundreds of charging ports, closing a portion of the gap toward the projected need of over 1,700 ports by 2030.

At the state policy level, direct incentives for commercial EV charging projects remain limited in 2026. Unlike many other states, West Virginia has not enacted broad tax credits or rebates specifically for businesses installing EV chargers; there are no statewide charger rebate programs currently offered by utilities, and incentives largely come from available federal tax credits that can offset installation costs for commercial ports rather than state benefits. While federal tax credits (such as the Section 30C credit) are available to businesses through mid‑2026 to cover up to 30 % of charging equipment costs, this is a federal benefit and not unique to West Virginia’s own policy. The state budget and legislative sessions have not moved major new funding measures aimed at commercial charging deployment, reflecting a cautious stance that prioritizes federal partnerships and planning over aggressive state subsidization.

Legislative debates in West Virginia around EV charging in recent years also reflect an ambivalence toward tightly regulating or strongly incentivizing commercial EV infrastructure. For example, a 2025 House Bill (HB 2095) proposed requiring all new public charging stations installed after January 1, 2026 to support universal charging standards compatible with most major vehicle manufacturers, but the measure stalled in committee and did not become law. This indicates some interest among lawmakers in shaping technical aspects of charging deployment, though not yet enough consensus to translate into binding policy. At the same time, separate 2026 legislation (HB 4586) seeks to restrict government procurement of electric vehicles, underscoring political tensions in the state around electrification more broadly. Together, these actions illustrate that West Virginia’s 2026 stance on commercial EV charging prioritizes federal program implementation with regulatory caution and limited state‑level incentives.

Solar Power in West Virginia -

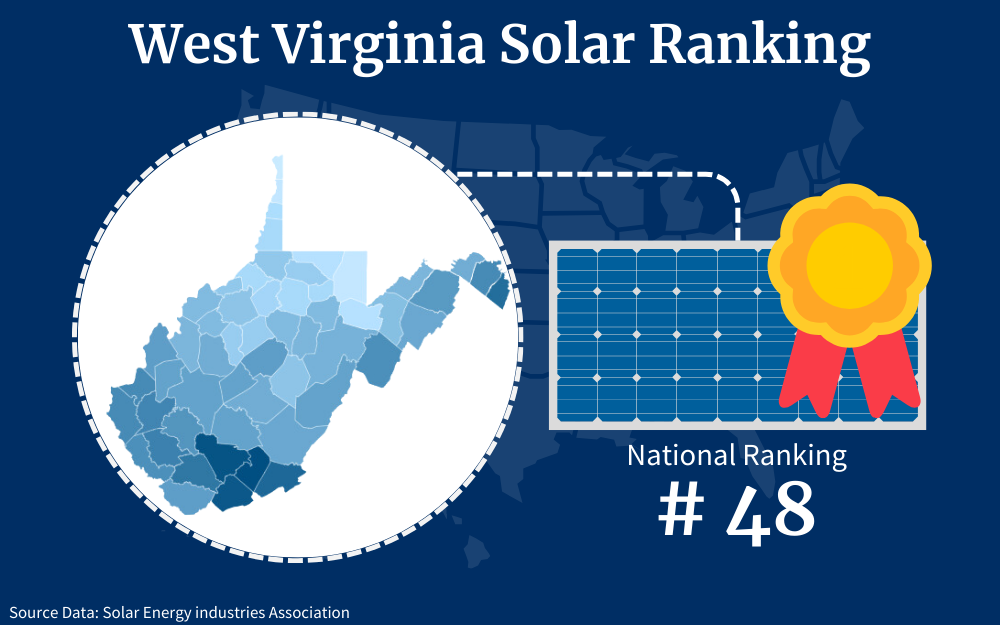

West Virginia’s stance on commercial solar in 2026 remains cautious. The state has no mandatory Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) and repealed its previous standard in 2015, limiting incentives for utilities to adopt solar. As of early 2025, West Virginia ranked 49th nationally in solar capacity with only 208 MW installed, enough to power roughly 20,000 homes. A 2026 legislative proposal, HB4684, would eliminate state tax credits for solar, signaling ongoing resistance to expanding incentives.

Commercial solar development is still progressing under existing frameworks. Utilities like Mon Power and Potomac Edison are building projects, including a 5.75 MW solar site in Berkeley County, with a pipeline of projects expected to total 50 MW. A LandGate analysis shows a queued solar pipeline of ~6,240 MW, highlighting developer interest. Most projects rely on federal incentives like the ITC, since state-level support is limited, and net metering policies remain critical to economics, though utilities have proposed reducing credits.

Regulatory and political debates shape the state’s approach. Utilities have proposed cutting net metering credits by nearly 70% for new customers, sparking pushback from solar advocates. Executive vetoes and cautious legislative action, like limiting project size increases, reflect concern about coal’s role in the energy mix. However, efforts like HB4111 to create a community solar framework indicate some policy movement to expand commercial solar access. Overall, West Virginia’s stance in 2026 is pragmatic but limited, balancing solar growth with coal industry interests.